The Rebecca Riots

Page added 22nd March 2016

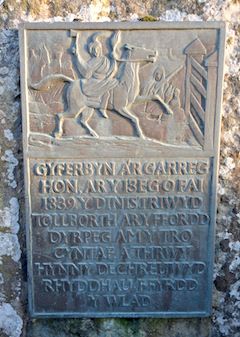

Plaque at the site of the first Rebecca Riot

The 1830s were a time of immense change. The Poor Law Amendment Act established the blackest of marks in British history with the introduction of the new Workhouse system; the Tithe Commutation Act crippled farmers. Charles Dickens had already become famous with The Pickwick Papers and Lord Melbourne was easing the stress of being Prime Minster and having as a wife Lady Caroline Lamb, by indulging in his favourite pastime of whipping orphan girls.

And to Pembrokeshire and west Wales came Thomas Bullin. Bullin had originated in the London area where he had seen the niche for becoming a ‘toll farmer’. This took the form of buying up financially strained Turnpike Trusts on the point of bankruptcy. The theory was that Bullin and others like him who took over such Trusts would maintain the roads out of the tolls being charged at toll gates and be allowed to pocket any profit, but in practice, Bullin pocketed all of the tolls and saw the chance for even more by erecting additional gates.

The gate that was erected by him in 1839 in Efailwen was the straw that broke the back of desperate farmers; this was the road that they used constantly to transport lime – the only fertiliser then in use. On the 13th of May 1839 a group of them appeared at the gate and destroyed it along with the toll cottage. But Bullin had another in place within days and many might have considered that the attempt to register their anger and desperation had been futile. Not so.

There appeared on chapel doors shortly after this event, posters advertising a meeting to be held on June 6th at 7.30pm, in the barn of the farm of Glynsaithmaen on the outskirts of Maenochlogddu. It was a remarkably audacious public notice that made no attempt to disguise where and when it was going to be held, and stated that the purpose of the meeting was to ‘discuss the need’ for the new gate at Efailwen. This in itself was cheeky, in that the farmers, little more than peasants, had no authority to ‘discuss’ anything to do with the roads and turnpikes.

There was an unwritten subtext to this poster which involved bringing to the meeting, women’s dresses, axes and soot with which to blacken faces. And late on the evening of the 6th June 1839, following the ‘meeting’ at Glynsaithmaen, 350 farmers from north east Pembrokeshire once more destroyed the gate but this time, and for the first time, in the costume that was to become their trademark – that of women’s dresses, some in bonnets with straw wigs.

The barn at Glynsaithmaen Farm

There was a third destruction in July, this time of a chain across the road instead of a gate and following this the magistrates instructed Bullin not to re-instate it. And that should have been it; the Efailwen incident was over, complete and successful.

But Bullin started it all again in 1842; this time the offending gate was to the east of St Clears. What followed was almost a year of continued escalation of riots as Rebecca and her daughters cut a swathe across south Wales.

Workhouses were attacked, being seen as much a contributing factor to the discontent as the toll gates, as was the disenfranchised position of 90% of the population.

Due largely to the sympathetic reporting of the Times correspondent Thomas Campbell Foster, reports on what was happening in Wales went around the world. Soldiers were brought in on a large scale and clashed from time to time with Rebecca and her followers but a remarkably successful guerrilla style of action ensured that the military were often left frustrated and empty handed.

The court room inside the Shire Hall

Despite this it was inevitable that some rioters were captured and the Shire Hall courtroom in Haverfordwest (currently on the point of being destroyed despite pleas from all quarters) was the scene of Rebecca trials.

Following a Commission of Enquiry chaired by Thomas Frankland Lewis, and various reports, legislation was introduced that changed the structure of Turnpike Trusts and eventually brought in County Road Boards.

In his concluding comments Thomas Frankland Lewis described the riots as a justified and well organised struggle against local injustice which would become known as, ‘a very creditable portion of Welsh history’.